Some months back I found out I had a refund check owed to me by an old dentist. It wasn’t a ton of money, but I, my Lego obsession fully rekindled, joked with my wife that I should spend it on Lego. And not just any Lego, but the biggest one I could come up with on the spot. The Eiffel Tower.

For those who don’t know, the Lego Eiffel Tower set is a whopping 10001 pieces and stands about five feet tall. With a nearly two foot square base, it’s a massive set. And it comes with a massive price tag. Far more than my piddly refund check could cover, and far more than my wife would allow without looking up how to draft divorce papers.

But the joke had been made, and I’ve never been one to let a joke go, good or bad.

So when Christmas rolled around and we got some cash with which to buy ourselves presents, of course I had to champion the tower. My birthday was the following month. Eiffel Tower please. We got our tax return. Eiffel Tower! No such luck. Not that I was actually expecting it.

But then one fateful day, my wife got a promotion, and with it, a pay bump. I was out of town when the news came in, so I texted her “Eiffel Tower?!?!?!” Her response was immediate.

”Sure.”

Apparently she’d already decided that each of us should treat themselves (she got official Barbie roller blades and other paraphernalia), and was just waiting for me to ask.

As you can imagine, after much agonizing and debate, I ordered the Eiffel Tower.

I knew the box would be large. But I didn’t realize exactly how large. The giant cardboard box left at my doorstep could have fit a couple of small children, or one of those window AC units. Pretty sure my 100 pound German Shepherd would have been cozy inside. I opened the box to find… another box. Talk about building suspense, Lego.

Inside that box was the actual box. The big kahuna. I immediately took a pic and sent it to my family, who of course all knew the ongoing joke and that it was becoming a reality. I got several messages that for some reason had similar concerns.

Don’t do it all in one day.

Well, considering it’d arrived in the afternoon, and there were baby bathes and kid bedtimes to handle and stuff like that, doing it that day was out of the question. Had I received The Eiffel Tower at 8am and before becoming a parent, it totally would have been a single-day build, blisters be damned.

Back to the box(es). I carried the shiny new box upstairs where The Eiffel Tower would stand when completed and opened it up. Only to find three more boxes. Sooooo much cardboard. Each of the three smaller boxes seemed larger than any other single Lego box I’ve ever had. My inherently faulty memory and in-the-moment elation may have influenced that assumption, but if it’s not true, it isn’t by much.

And now: time to build.

Normally I do builds on the dining room table. But that’s downstairs, and no way was I going to carry a five foot tall tower up the stairs and risk it falling or smacking into something. So I built it. On the floor. I’ll be 40 years old next year. Do you know what sitting on hardwood floors for hours on end does to a middle-aged body? Let’s just say I was more sore from one night of building on the floor than I was from doing the world’s largest bouncy house non-stop with my kid for three hours.

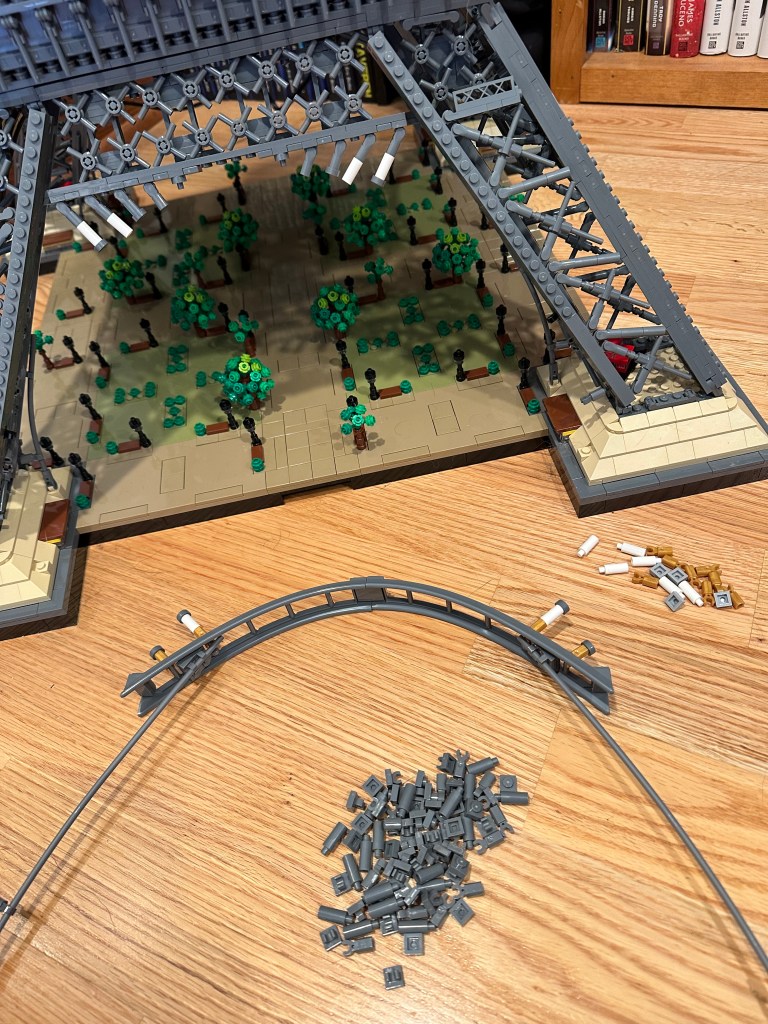

Evening one was just the base and the first layer of supports. Those trees got a bit monotonous, along with the trusses running up and down the legs of the tower. Especially the trusses. I was a little confused as to the red and yellow pieces on opposite legs, but it made sense once I resumed the next day.

Build evening number two was cut short for reasons, and I was only able to get up to the blue pieces, not the smaller section of tower standing next to it. Part of the delay was just family stuff. Another part was something new for me with Lego sets.

Everyone so often there’ll be a piece missing from a set. Something at the factory didn’t go right and a small 1×1 plate will be missing. Lego is great as sending replacement parts if this happens, and it’s never really been a big deal, especially when my sorted inventory of pieces has a replacement I can use. This time, it wasn’t just one piece missing.

As most Lego builders know, there are numbered plastic bags that you open in order as you progress through the set. Inside those bags will sometimes be smaller plastic bags filled with a bunch of really small pieces. Bag 32 was once such bag. There were multiple small bags within. The only problem was that one of the smaller bags was the wrong bag. What that meant was I was missing not one, but ninety-six pieces. On the plus side, the wrong bag that was in there ended up being entirely extra pieces that found their way into my bins for future projects.

But I was missing a lot of pieces. What was I to do? First, I tried to find replacement parts for all the pieces. That sort of worked. All the pieces were that same dark grey color. I had plenty of the right type of piece, just not enough in dark grey. So The Eiffel Tower got a temporary paint job.

Each of the four sides looked like this. Luckily, this section wasn’t structurally significant, so when the replacement pieces arrived, swapping them out proved not too difficult.

When you go to the Lego site to request a missing piece, it’s an easy and basic form to fill out where you can look up the piece, enter your info, and boom, it’s on its way. But it was designed to replace one or two pieces at a time. Not ninety-six. Looking up and adding those one at a time would have taken forever, so instead I emailed customer service and explained the situation. After a couple of emails back and forth, the pieces were on their way. Super helpful and understanding.

While the actual, fully complete Eiffel Tower took a couple of weeks because of the replacement parts, I built the (with replacements) whole thing over three evenings. Part of me wanted to see if I could speed build the thing. I looked up the record for the set’s fastest build, and it is 9 hours, 14 minutes, and 32 seconds. I didn’t use a stop watch, but even with the hunting for replacement parts and constant shifting on the floor as my hips let me know how unhappy they were with my life choices, I don’t think I was too far off from that mark. If I assembled everything from a comfy chair at the table and had the proper pieces waiting for me… it could happen. I’ve always thought I was a speedy builder, and if I ever felt like disassembling and reassembling all 10001 pieces, I might have to give the record a go.

Now that it’s completed, it’s standing tall in the corner of my office. Before it arrived, I had briefly thought about using it as a bulletin board, hanging up character and plot ideas for later, but once I assembled it I realized the top was far too narrow for that. So instead I just have to lean this way or that to see my whiteboard notes. I can live with that. 🙂

Oh, and the red and yellow pieces? Elevators to the various observation decks. Zoom in and you can see them at intervals inside the tower. And lastly, all Lego sets are built using the same catalog of pieces. The colors can be changed easily enough, and yes, they’ll occasionally make new pieces for sets if needed. But there’s a thing called nice part usage, where you take a piece and use it for something other than what it was designed for. My favorite nice part usage in this set was the sausage. The thirty-two sausages.

Because of the Paris Olympics I really want to surround this with micro-builds of Olympic events. But I’ve not nearly the time or bandwidth for that. Sad. But that’s all for today. Hope you enjoyed my little journey, and if you’ve any fun builds or Lego stories to share, feel free.