For anyone who has had more than two conversations with me, it’s no secret that I’m a huge Borderlands fan. This is the game that got me into first person shooters. Borderlands 2 is only the second game that has made me walk away because of emotional storyline choices (FFVII popped that cherry in high school. Damn you Sephiroth). Borderlands has also provided my best multiplayer story experience (sorry Mario Kart and Smash Bros, you don’t really have a story).

So when this movie was announced years ago, I was excited. Very excited. Then the casting began. Jack Black. Cate Blanchett. Jamie Lee Curtis. Kevin Hart. Yes. This was going be amazing. Was I a little concerned about Cate Blanchett’s age in regards to Lilith? Yes. Did Kevin Hart’s height seem surprising given the massive physical presence Roland had? Of course. But having seen Cloud Atlas become a movie and Wheel of Time become a show, I was open to interpretation.

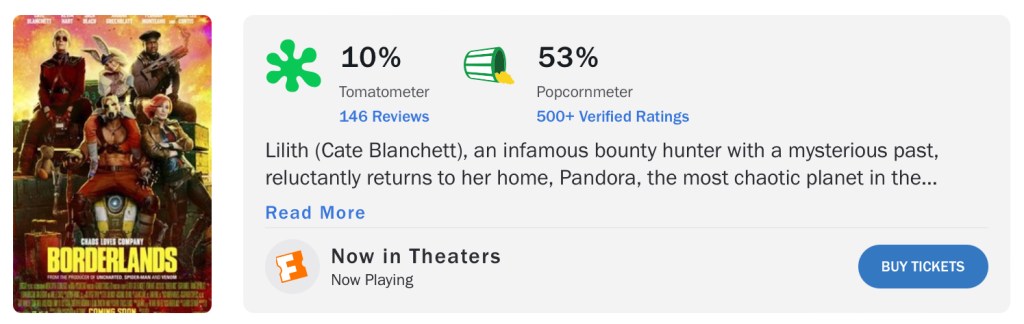

As well all know, the movie has been utterly destroyed by critics. Disheartening. On pace for one of the worst movie releases ever. Dream-shattering. But that created the perfect silver lining. If I went into it thinking it would be an abomination, then I was likely to enjoy it more than if I’d super-hyped it up. Right? Right?!

Borderlands was not a good movie. It wasn’t a terrible movie either. It was just a bad movie. The beginning was particularly bad, though it did get better as it went along. Why? I’ll point out very specific reasons that someone in the writing or editing process should have picked up on.

Warning! Spoilers are coming. I’ll try to only hint at big reveals in case you haven’t seen it, but I won’t be able to talk about this spoiler-free.

Problem One: Pacing.

This movie did not know what it wanted to be. Comedy/action? Straight action? Potty humor? Now, I’m not privy to exactly which parts were involved in the reshoots, but I’d wager a healthy sum it was focused on the beginning. It started out with Cate Blanchett exposition regarding Eridians and the Vault and for someone knowing nothing about the world of Borderlands, that would be very helpful. Part of me thinks they were trying to replicate her intro narration in LOTR. It didn’t work out.

The problem with narration is it slows everything down. Borderlands is a first person shooter. The most effective parts of this movie were when they leaned into that freneticism (something I’m assuming attracted them to director Eli Roth). The second problem with narration in film is that it’s often the sign of bad/lazy writing.

There are three moments of narration. The very beginning, a random bit maybe fifteen minutes later when Lilith gets to Pandora, and then a bit at the end. The middle narration was completely unnecessary. She tells us something happened, then we watch it happen. Then she tells us something happened, then we watch it happen. There’s that problematic writing axiom, show don’t tell. Regardless of how you feel about that, you definitely don’t do both at the same time.

The end narration was one of those contrived, moral of the story bits. No, it didn’t have a moral, but it told you how you were supposed to feel about what happened and where things were going. Audiences (arguably) aren’t dumb. We can form our own opinions. Don’t belittle us with that garbage.

The middle and ending narration were bad and shouldn’t have been there. That leaves the beginning narration. Can you have just the one segment of narration. Yes. Will the film be stronger without it? Probably. The reason I don’t like narration and find that it’s lazy, is most of the time that information can be conveyed during the action of the movie. We heard plenty of times that the Eridians were no longer there, that they left tech behind, and Vault Hunters sought the missing vault on Pandora. That takes out the entire opening narration right there.

The one other pacing thing I’ll mention, not even talking about the actual cutting and editing of the sequence of events, is as it relates to the tension of a scene or moment. Very serious, awe-inspiring Lilith flying around with fire wings? Probably a good time to throw Krieg in there with a 1.5 second gag line. Then back to the seriousness. What? Really? Who thought that was a good idea?

Problem Number Two: Continuity.

I imagine (or hope) much of the blame for this lies in the need for reshoots. Basically, there were several payoff moments toward the end of the movie that called back to earlier scenes in the film. The one that stands out the most was when Tannis offered Tina some tea. You could definitely tell this intimate moment was set up earlier. Except it wasn’t. I’m sure at some point there was a scene or set of lines involving Tannis and Tina and tea, but those lines didn’t make it into the final cut. The problem is that the emotional impact of the lines we did see was non-existent. Instead of an “awwww” derived from character growth, we just wonder why the celebration scene is being interrupted with tea? Every second of screen time is important. Why waste ten seconds on that line when it doesn’t mean anything to the audience.

Also, and this stemmed from an in-game joke, when they got to Sanctuary they all had to go up some stairs. I asked my friend at the theater, “how’d Claptrap get up the stairs?” And we both chuckled. Then later on there were stairs again and Claptrap started to do his “oh no, stairs” bit, and Krieg grabbed him and carried him. So they addressed the question/problem, but not when the question/problem first arose. Take the Sanctuary stairs out… perfect. Or have Krieg carry him in Santaury… works great. Ignore the stairs entirely and then do the stairs joke? Continuity problems. Things happen in an order for a reason. Understand those reasons.

Problem Number Three: Appropriate Level of Fan Service.

I admit this is a broad topic. In adaptations, anything and everything can be considered fan service. For the sake of this, I’ll break it down to three aspects: locations, dialogue, and characters.

I’ll start with the least offensive: locations. I actually quite enjoyed seeing the world of Pandora and everything that was included. From named locations like Fyrestone and Sanctuary, to the exact placement of bones where that one badass skag always comes from, or the fact that they jumped over Piss Wash Gully, those visual treats were subtle and hit the fandom just right. Now, did it make sense for them to brave the Caustic Caverns only to stumble across a bandit stronghold whose denizens clearly didn’t use the caverns to get there? Not one bit.

Next: dialogue. Knowing first-hand how hard acting is, I don’t want any of this to seem a judgment on the actors. I’ve said for a long time that the greatest struggle for independent films is good writing, followed by good audio, but that’s another issue. That being said, were there times when Eli Roth should have said, “Okay, let’s try that one again?” Yes. Beyond that, there were moments when Easter eggs were thrown into dialogue at the expense of the quality of the dialogue.

For example, there’s the moment when Lilith realizes she needs a vehicle, so she says she’s gotta “catch a ride.” That’s straight from the game, but it sounds utterly ridiculous in the moment. Another time, Tina asks Lilith to grab her badonkadonk. Another reference straight from the game. With the right setup, it might have worked. But it didn’t. Even knowing what that meant, the execution was terrible. Fans like having those moments appear in film and TV, but it has to be organically integrated, not shoved in half-assed. We want to experience the world. We don’t want you to wink at us every time you think you’re clever.

And speaking of Tina, though off topic, let her blow stuff up! That’s what Tina does. Sure she throws some grenades at the end, but she gave Bob to Roland, and the few explosions when we meet her seem situational, not character driven. Tina is bat-shit. Let us see that.

That leaves us with characters. I’m going to point out two poor choices, and two good choices. The poor choices (and there were more than just two) are Marcus and Krieg. It’s tricky, adapting a world with so many characters that so many people love. I understand wanting to satisfy everyone, but it can’t be at the expense of the story. Marcus had two real scenes. The first was picking up Lilith on the Vault Hunter bus. That is a classic callback to the first Borderlands game, and technically it served as a vehicle *ahem* to learn about Lilith’s feelings about Vault Hunters. But it ate up a lot of time and added nothing new to the story. We knew Lilith thought Vault Hunters were dumb. It played as an awkward scene shoved in for the sake of seeing the bus. His second scene was trying to barter with the Crimson Lance. That’s a perfect use for Marcus. Give him three lines (not just a split second visual like with Ellie). Show the audience that the people of Sanctuary stand together against the Lance. Advance the plot as our heroes try to escape. For people who know Marcus it’s “hey, it Marcus!” For those who don’t, it doesn’t matter. Because it adds to the world in a way that advances world-building and story at the same time, without taking us out of the moment.

The second poor choice was Krieg. I understand wanting the big dumb brute as a foil for pretty much everyone else, though the main contrast is with Tina. The problem is this big dumb brute lacks a face, only shouts, and only speaks in caveman garble. Combine the garble with shouting, and half of what he says (and that’s generous) is unintelligible. Does unintelligible dialogue advance plot or character or anything? No. Does a primary character with zero facial expressions work? Almost always, no. But I do like the idea of pairing a sensitive brute with a small child. Luckily, Borderlands has just the person for that. Brick! He’s big, he’s dumb, and man is he protective of Tina. Not only would we have understood him, but we would have seen actual emotion. And he could have addressed why he was on that Atlas ship in the first place.

There were two good character inclusions in the movie. The first is obviously Lilith. As much as she was underwhelming in the first game, her role in the subsequent games can’t be overstated. And then there’s Roland. Remember when I mentioned Borderlands 2 was one of the two games that made me emotional enough to walk away? Roland. God damn you, Handsome Jack.

In Lilith we get a central character that is meaningful for the gamers, while also being a fairly well-realized cinema character. Adding her mother (completely wasting Haley Bennett) and showing her prior connections to Tannis and Moxxi worked very well and her character arc in the movie was one of the best parts. Also, when she goes full Firehawk… hits the nostalgia so hard.

In Roland we get the jaded ex-corporate soldier. Roland’s character arc was lacking, likely due to the fact that he was intended as a supporting character to Lilith and Tina. But he was a great choice as a character to include. With better writing, we could have seen the corruption of the corporations (also negating the need for intro narration), and Roland’s setup as a Pandoran leader would have made sense on a practical and emotional level. There’s a reason his character was so pivotal in Borderlands 2. A sad note about him though… we never got to see him deploy hit turret. We see plenty of cool tech, and there are a couple of battles it would have been great in. Lilith got to phasewalk. Kreig almost always rampaged. But no turret for Roland. Missed opportunity.

These three problems I’ve addressed aren’t the only problems in the movie, they’re just three of the most obvious, and most easily fixed. The ease with which they could have been addressed is especially frustrating after waiting so long for this movie to exist. But it at least provides solace in knowing that a Borderlands movie won’t inherently be garbage. There is so much lore to pull from and so much opportunity for engaging storytelling, even if the movie doesn’t follow the game’s story.

TLDR: The movie was bad, especially beginning. Pacing, editing, and character usage were major problems.

I should say that the fights worked well, especially with the bandits in the tunnels and the main fight at the end. The chaos and unrelenting horde of meat fodder was very reminiscent of the game and very fun.

Would I watch it again? Maybe when my kid is old enough. Maybe just in the background so I can glance at nostalgic scenery. And, because I’m eight-years-old, watching Claptrap violently diarrhea bullets will never get old.

PS: When Roland breaks Tina out at the beginning, that was totally the perfect moment for a “little short for a Crimson Lance” joke. Right in line with Borderlands and much funnier than the short joke they put in later.