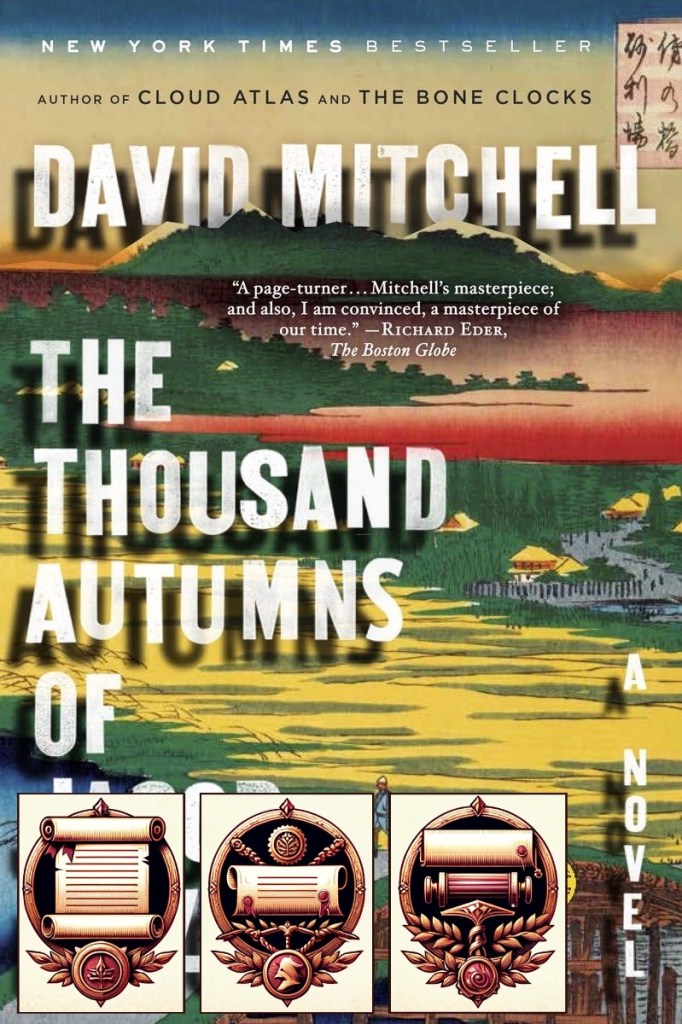

Welcome back for another book review. I want to preface this with an admission of the chance for bias. David Mitchell is one of my favorite authors, perhaps even my favorite, though it’s really hard to choose. One of my short pieces I plan to shop around once I think it’s good enough is actually about him. With favorites, there’s a tendency to overlook faults or take strengths for granted. I’ll try to do neither.

You may wonder why, if Mitchell is one of my favorites, I have not yet read The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet until now, when it’s been out for well over a decade. Circumstance and poor luck. Shortly after it came out and I acquired it, I moved. It went into one of many boxes, and most of those didn’t get unpacked for a while. By the time they did, I found a box had disappeared in the move, along with half my Mitchell books. I assumed they’d show up and then I’d finish reading it, but eventually I gave up hope and just now reacquired it.

That out of the way, let’s get to it. A spoiler-free review of The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, by David Mitchell.

The Thousand Autumns (I’ll refer to the novel thusly to save space and prevent finger strain) follows three primary characters: titular clerk Jacob de Zoet, unlikely medical student Orito Aibagawa, and Japanese-Dutch interpreter Uzaemon Ogawa (I’ll order Japanese given and family names as we’re used to in Western culture to prevent confusion). Set in Dejima, a trading enclave in Nagasaki, Jacob is trying to make money so he can marry his betrothed back in the Netherlands. He meets Orito by chance, and Uzaemon for need of an interpreter.

What starts off with the makings of a love story morphs into a story with ever expanding scope and the mysticism/magic you’ve come to expect in a Mitchell novel. Things are never as they seem, nor are people. More so of course than is expected anyway, as that sentiment can be applied to nearly every person or character.

Throughout the story, all the characters are faced with trials of morality and ethics. None as much as Jacob, Orito, and Uzaemon. Sometimes strong ethics serve a person well, other times they hurt. The ramifications of those choices drive the narrative as well as the whole Nagasaki region.

A few aspects I want to highlight in particular are setting, prose, and character. Let’s start with setting.

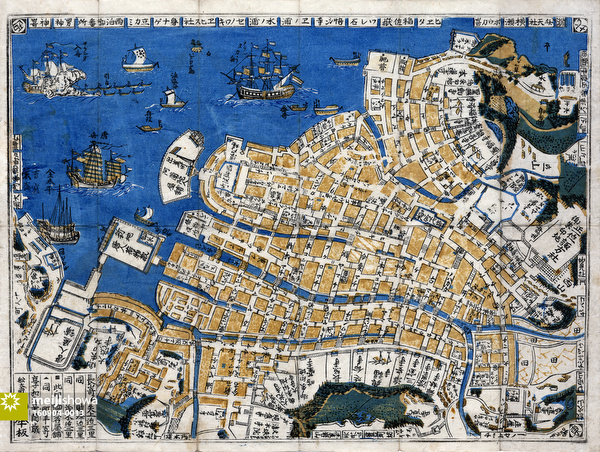

When I was in school, the foreign language I studied was Japanese. My wife also studied it, though she lived in Japan and focused more on the culture and history than I did. She read this book and said she found the setting boring because she already knew about the era and life of the Japanese and their policies regarding trade and foreigners and all the details were old news for her. What that tells me is that Mitchell has done his homework.

As a fan, I know that Mitchell has spent time in Japan as well and speaks Japanese, so it’s no surprise his knowledge of the language, culture, and history are so accurate. As someone who focused more on the language and less on the other aspects, I found the portrayal to be enlightening, the dynamics of Japan’s isolationism 200 years ago tremendously interesting and mind boggling at the same time.

There are true events woven into the story, like the attack of the British in Nagasaki, what I assume to be the Great Kaga Earthquake, and of course the warring European nations. These moments ground the reader in the reality of the world which serves to both strengthen the impact of Mitchell’s story and also highlight his unique book-to-book connections.

Moving on to prose, Mitchell was aided in that he was able to draw on Japanese symbology and propriety to help order rich, authentic words such that the sentences seemed foreign and familiar all at once. I noticed in particular a tactic of interspersing descriptions of setting between spoken words and actions that I don’t recall in his other writing, and that’s having just read Utopia Avenue a few months ago.

I haven’t the audacity, nor experience, to try and accurately portray another living culture’s mannerisms speech patterns, and when Mitchell does so in The Thousand Autumns, I never felt for once that he was stereotyping or using unusual vocal patterns as an interesting crutch, relying on the foreign sounds or diction to engage the reader. When Orito or Uzaemon spoke, their words read authentic and true, which is no small task. That holds true with their thoughts as well.

Lastly, before I go into craft, I want to mention a brief thought on my reactions to character. Talk to anyone who knows me, and they’ll tell you I’m not outwardly emotional, perhaps bordering on sociopathic. That’s a bit of an exaggeration, but the point I’m trying to make is that I’m rarely emotionally responsive. For me to react emotionally to a book says something about its efficacy. (Unless we’re talking about rage quitting. Non-effective storytelling there. I’m looking at you Ready Player One)

There’s a moment, and I’m being vague to avoid spoilers, where Jacob has to say goodbye to someone. I got choked up. Like, tight throat, sniffles, the whole shebang. The moment wasn’t an overly dramatic profession of love, or a heart wrenching death of a beloved character, but a simple goodbye. The reaction this moment elicited could only have been achieved through solid portrayal, and thus investment from me, of the character Jacob.

Okay, on to craft talk. Today’s topic: Research.

I touched on this earlier in setting, but wanted to expand beyond the scope of The Thousand Autumns. I can think of few exceptions where research would not be necessary for a novel. I’m sure Neil Gaiman had to dig through tons of myths and religions when he wrote American Gods. Or Cherie Priest had to find maps and records of 1880s Seattle for her Boneshaker books. Research lends credibility to a story, but it also grounds the reader in the world.

Imagine you’ve picked up DaVinci Code and you’re following Robert Langdon through the Louvre and Dan Brown throws in something about racing past Rodin’s The Thinker on his way to the Mona Lisa. Dan Brown is pretty sure The Thinker is in Paris, and the Louvre has all the cool stuff, so it’s probably there. Spoiler: It’s not. It is in Paris, but it’s at Museé Rodin, not the Louvre.

The magic of DaVinci Code is all the research that makes the story, the interconnected bits of history, engaging the reader with history. Every place Langdon visits is real. I actually have an annotated copy of the book complete with photos and illustrations of the sites and pieces of art. Few people will know every art and history reference in the book, but having that information there raised the reading experience to a whole new level.

Research gives validity to the world of your story. And it doesn’t matter if your world is Earth or Mars or Xanth or something I’ve never heard of. Sometimes research it just finding the proper details. I’m working on a story where the protagonist is a carpenter and I had to learn how to build a chair with medieval era tools. I already knew how to with modern tools, but I can’t exactly have my character whip out a cordless drill. Or there was the story of mine just published in Space Brides. Exactly how bright is Jupiter if you’re standing on Europa? How far does that elevator ride through the ice need to be? Research.

I know sometimes research may seem like a slog, that every page you get to poses a new question that interrupts your flow. One trick is to throw a placeholder in so you can keep writing and do the research later. For months I had “HE BUILDS A CHAIR” followed by the rest of the scene. Another is simply read a ton about what your character knows or experiences before you write and you can just go with it. Or, if you’re David Mitchell, go live in Japan for a decade. To each their own. 🙂

I can’t really give advice as to how to best do research. That depends on you and your story. But I can’t stress enough the importance of it. We’ve all heard of the seven basic plots that all stories follow. What separates those stories from one another are the details. We get those details from research. Details enrich the reading experience and color your worlds. Find those details. Do the research.

Now, time to break out the Author’s Arsenal and throw some accolades at The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet.

For accurate linguistic depictions and line to line pacing, I award The Parchment. For making me emotional and balancing culture with agenda, I award The Seal. And for the research, for bringing an accurate (of course accounting for factionalized elements) world of turn of the 19th century Japan to his readers, I award The Scroll.

For those who have not read David Mitchell, these awards should not be surprising. His novels are regularly long and short listed for awards, and the varied settings and times they take place in always present something new. My first exposure to him was Cloud Atlas. It is my favorite book of all time. Just phenomenal. But, if you’re thinking about reading The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, don’t. At least, not first.

I needed to put in here somewhere that most of his novels are loosely (some not so loosely) connected. You technically could read them in any order, but I think what makes the most sense (and my google search confirms my thoughts) is that you should read them in order of publication. That would mean Ghostwritten, number9dream, Cloud Atlas, Black Swan Green, The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, The Bone Clocks, Slade House, and Utopia Avenue. For me, the weak link was Black Swan Green, but I know those who really enjoyed it.

Hopefully this review will have made a new Mitchell fan or two. Until next time, happy reading, and if you have any books you’d like me to read and review, let me know.

The Quill Pen. This will be awarded for exceptional storytelling or narrative.

The Quill Pen. This will be awarded for exceptional storytelling or narrative. The Inkwell. For depth and richness of theme.

The Inkwell. For depth and richness of theme. The Parchment: For the quality of writing style and prose.

The Parchment: For the quality of writing style and prose. The Seal. For character development.

The Seal. For character development. The Scroll. For world-building and setting.

The Scroll. For world-building and setting.